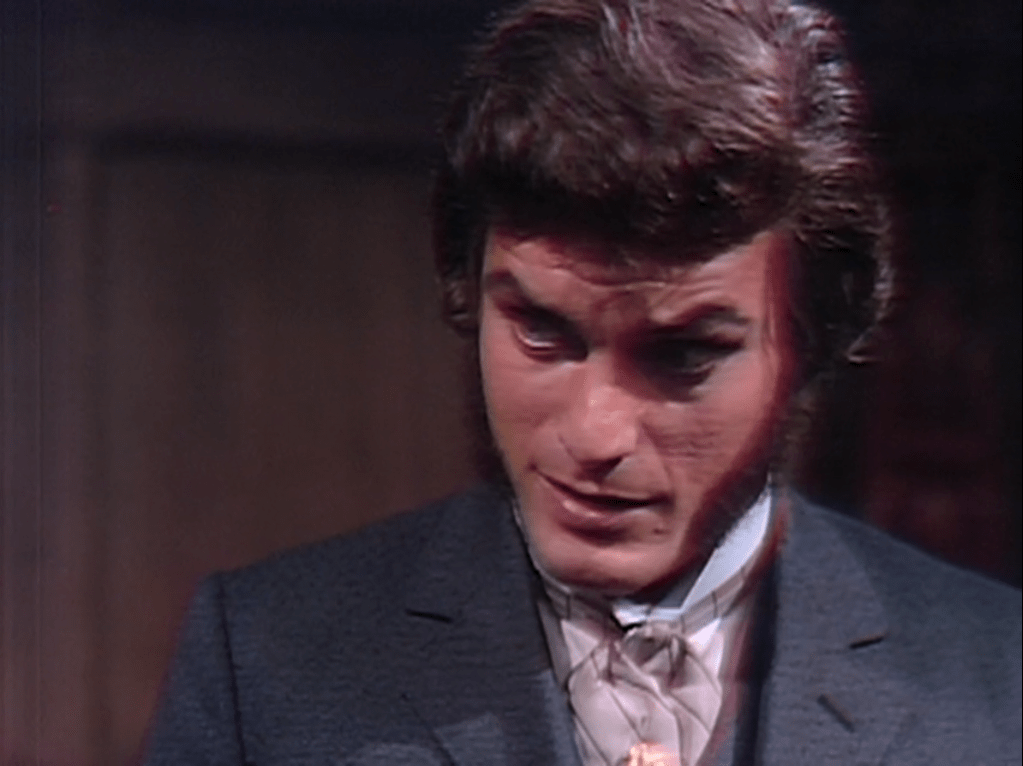

In October 1897, sorcerer Count Petofi has used his powers to steal the body of handsome young Quentin Collins and to trap Quentin in his own aging form. I refer to the villainous Petofi who looks like Quentin as Q-Petofi, and to the forlorn Quentin who looks like Petofi as P-Quentin.

We open outside a cave near the estate of Collinwood, where Q-Petofi’s henchman Aristide is on the ground, gradually coming back to consciousness. Q-Petofi had ordered Aristide to hold wicked witch Angelique prisoner in the cave. Shortly after Q-Petofi left, Angelique slipped out of the cave and ran past him. Aristide followed her, and she bashed him on the head with a rock.

Aristide’s eyes focus, and he sees time-traveling vampire Barnabas Collins standing over him. The last time he saw Barnabas was in #842. Barnabas threatened to kill Aristide then, and he was so terrified that he ran away and didn’t come back until he heard that Barnabas had been staked in his coffin. The coffin is in the cave, and Aristide just saw Barnabas in it, the stake still in his heart, so he is shocked to see him up and about.

We cut to the great house of Collinwood, where Q-Petofi and Quentin’s stuffy but lovable brother Edward are recapping another storyline. Edward exits, and a telephone call comes from Ian Reade, MD. Dr Reade says that a strange man is in his office, asking for Edward. When he describes the man, Q-Petofi recognizes him as Barnabas. He takes a gun and goes to Dr Reade’s.

Q-Petofi finds Barnabas lying on Dr Reade’s exam table. He orders Dr Reade to leave. Dr Reade reminds Q-Petofi that they are in his office and refuses to comply with his commands. He does leave for a moment to call Edward again; when he comes back, he finds Q-Petofi holding Barnabas at gunpoint. He bravely tells Q-Petofi that if he wants to kill Barnabas, he will have to shoot him first.

Edward comes. Dr Reade trusts Edward and agrees to leave the room while he is there. After dawn breaks, Edward is astonished to see that Barnabas is still alive. Barnabas tells his old story that he is their cousin from England come to pay his respects. He says that when he first arrived, a man approached him in the dark woods, a man who, when he emerged from the shadows, proved to be his exact double. Until, that is, he opened his mouth and showed two long fangs. Barnabas says that he does not know what happened next or how much time has passed. All he knows is that this strange man kept him captive and dominated his will, from time to time appearing to him and repeating his original assault.

Edward is inclined to believe this story, Q-Petofi to shoot Barnabas on the spot. They compromise, and agree to take him to the cave. If Barnabas’ coffin is empty, they will shoot him. Dr Reade sees Edward and Q-Petofi carrying Barnabas out of his office, and objects that in his condition Barnabas may die if he is subjected to any exertion. When the question is asked if he is willing to go, Barnabas weakly croaks out a “yes.” At that, Dr Reade is willing to wash his hands of the whole thing. For someone who was willing to be shot a few minutes before, it’s quite a startling capitulation.

Q-Petofi does not know that Angelique and Aristide are no longer in the cave, so he insists on leading the way in. He finds that they are gone and the chains around Barnabas’ coffin have been broken. He invites Edward and Barnabas in. He takes it as obvious that the broken chains prove that the coffin is empty, but Edward, with his sense of fair play, insists on opening the coffin before they shoot Barnabas. The body is still there, the stake still in the chest. Barnabas reacts with horror, the others with amazement.

In #758, Angelique created a Doppelgänger of herself to trick an enemy into thinking that she had killed her, and in #842 she agreed to help Barnabas’ friend Julia Hoffman, MD in a plan to allow him to reestablish himself as a member of the Collins family. Julia was working on a medical intervention to free him of the effects of vampirism, and now we can see that Angelique contributed the grounds for the Collinses to believe that their cousin never labored under that curse.

When Dark Shadows was in production in the 1960s, the legends of King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table, and the Holy Grail had been fashionable topics in English departments for decades. That vogue was reflected not only in the coursework the writing staff likely did when they were in college, but also in the popularity of novels like The Once and Future King and the Broadway show based on it, Camelot. When I was hanging out in used book stores in the 1980s and 1990s, mass market paperbacks printed in that era collecting the Grail sagas were still a staple.

The coffin in the cave recalls a prominent figure in one of those sagas, a king named Amfortas. In Heinrich of Turlin’s The Crown, Amfortas did not requite the love the mighty sorceress Orgeluse had for him. The humiliated Orgeluse inflicted a wound that both paralyzed Amfortas and made him immortal. In that state, Amfortas was confined to a coffin that was hidden in a cave. Sir Gawain found the coffin and freed Amfortas both of his paralysis and of his immortality.*

Longtime viewers of Dark Shadows will see many parallels to the story of Barnabas and Angelique in Heinrich’s story of Amfortas and Orgeluse. During the part of the show made and set in 1968, two mad scientists played the role of Sir Gawain in returning Barnabas to humanity. The first was a man named Eric Lang, the second was Julia. Now, Angelique herself, who was the original source of the curse that made Barnabas a vampire, combines the functions of Orgeluse and of Gawain. She not only frees Barnabas, but also redeems herself. The Grail legends also abound in other elements that figure prominently in this part of the show. For example, Count Petofi was originally on the show as a severed hand with magical powers, later to be reunited with the rest of its body. Gawain’s most famous story is of his battle with the Green Knight, who starts off as a severed head. Doppelgänger abound in the Grail legends, especially the so-called Vulgate Lancelot where a double of Queen Guinevere sets off a whole arc.

Dr Reade is played by Alfred Hinckley. Hinckley was in plays on and off Broadway, and when the networks ran a lot of programming produced in New York, his was a frequent face on American television. He was in Dark Shadows episode #1 as the conductor of the train that brought well-meaning governess Vicki Winters and dashing action hero Burke Devlin to Collinsport. Longtime viewers were reminded of that train in #850; maybe the production staff was reminded of it too, and that was why they called Hinckley to make his second appearance on the series today. It’s also his final appearance.

*Richard Wagner’s opera Parsifal features another version of the Amfortas legend, calling the sorceress by a different name, omitting Amfortas’ paralysis, leaving out the coffin in the cave, and giving the honor of healing Amfortas and succeeding him as king of the Grail to Percival rather than Gawain.