Dark Shadows did not air on Christmas Day, so no episode premiered 56 years ago today.

Dark Shadows did not air on Christmas Day, so no episode premiered 56 years ago today.

No episode of Dark Shadows premiered 56 years ago today. Instead, the ABC television network showed football, as is traditional on the USA’s Thanksgiving Day holiday.

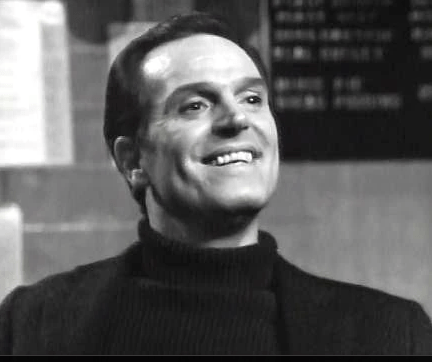

I see I haven’t yet linked to Dark Shadows and Beyond: The Jonathan Frid Story, the documentary film that Frid’s dear friend and longtime business associate Mary O’Leary made in 2021. Any fan of the show who hasn’t seen it should do so at the earliest opportunity. It’s available on many streaming platforms; if you don’t mind commercial interruptions, you can watch it for free on Tubi.

If you look at discussion boards and comment sections on fansites that were up before the movie was released, you’ll see people going round and round at incredible length about whether Frid was gay. We all owe Ms O’Leary and her collaborators a debt of gratitude for confirming that he was and thereby putting a stop to that pointless wrangling once and for all.

Frid was often called a “Shakespearean actor” when Barnabas was a big presence in pop culture. The documentary shows that while he was never the Shakespeare specialist this title would suggest, it isn’t exactly wrong to call him that. He did spend a lot of time on Shakespeare as a student actor in Canada and in England, each of his appearances in a Shakespeare play marked a definite turning point in the development of his style, and his one turn as a director was at the helm of a production of James Goldman’s pseudo-Shakespearean The Lion in Winter. He brought a distinctly Shakespearean tone to all of his works, allowing Dark Shadows to hold our attention even when the stories are as silly as the plots of Elizabethan comedies.

The movie also shows how deeply Canadian Frid was. He grew up in Hamilton, Ontario, son of a prominent businessman and civic benefactor. The discussion of H. P. Frid leaves us with the thought that social prominence in Canada is rather a different thing than it is south of the border. Old Mr Frid seems to have occupied a lordly place that would not have been possible where the USA’s single market pulls even the most remote town into the swing of national life and presents constant reminders that the local bigwigs are themselves somewhere down the pecking order from grander figures elsewhere. Young John Frid may have pursued a career on the stage to escape his father’s shadow, and it is no wonder he had to go abroad to accomplish that.

While in England as a student at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts and then as an actor in regional theater, it was his North American identity that dominated people’s perception of him. For all that Canada had the same monarch who put the “Royal” in RADA’s name, in Frid’s appearances on the English stage was usually cast as a US national. And after his fame in the USA and period of residence in Mexico, Frid did go back to spend his final years in Canada. The footage of him there shows him at home in a way that he never was anywhere else.

No episode of Dark Shadows premiered on ABC-TV 56 years ago today. The network pre-empted Episode #891 to show news coverage of the end of the Apollo 12 mission.

All three astronauts who traveled aboard the Apollo 12 spacecraft were officers in the United States Navy. When I was a teenager, I assumed I would go into the armed services. The Navy was the only branch that did not immediately reject me because of my various medical problems. They gave me several waivers, but finally declared me unfit for military service because of my astigmatism. So I went to college instead.

Even so, I still have a certain feeling of attachment to the Navy, enough that Apollo 12 is my favorite of the lunar landings. The mission’s official patch is kind of embarrassing, like something you might find on a box of Cap’n Crunch cereal, but here it is anyway:

No episode of Dark Shadows premiered on ABC 56 years ago today, since the network had decided to cover the visit of the Apollo 11 astronauts to Chicago instead. So I’ve decided to take this opportunity to link to videos of some interesting discussions about the show posted on Youtube.

They couldn’t have in-person conventions with panels including original cast members in the year 2020, what with Covid-19. So they had a big Zoom call instead. That one is especially interesting, because it brought out some people who hadn’t made themselves visible to fandom in decades. In the case of David Henesy, it may have been his first act of fanservice since the show went off the air. When Alexandra Moltke Isles says that her first encounter with a fan was with someone who grabbed her hair and tried to rip it out of her head, that absence is perhaps understandable. The video shows the meeting in speaker view. Fans who groan every time Roger Davis turns up will find it grimly appropriate that he couldn’t figure out how to mute his camera, and so he keeps flashing in when other people have the floor. I can’t embed it, but here is the link.

Another Zoom recording some might enjoy seeing is of an April 2021 gathering in honor of Danny Horn’s great blog Dark Shadows Every Day. I was there, under my off-screen name. The discussion got a bit awkward when some podcasters started vying with each other and with the actual host to take over the moderator’s role, but I think all of us who wanted to do so eventually made ourselves heard. It was a good time.

Since 2020, Dark Shadows fan gatherings have taken on the character and often the label of memorial services, since so many of the people who used to appear on the panels are either deceased or otherwise unable to travel. But some of them have maintained a jolly spirit even so. For example, in this 2024 panel appearance Marie Wallace and Donna Wandrey amusingly complain about some appalling behavior by director Henry Kaplan. Sharon Smyth, who wasn’t on the show when Kaplan was, listens.

This July, Danielle Gelehrter hosted Kathryn Leigh Scott and David Henesy for a Zoom chat under the aegis of her “Terror at Collinwood” podcast. Mr Henesy has his own stories about Kaplan’s misdeeds.

I wouldn’t want you to think that Mrs Acilius and I watch nothing but 56 year old TV shows. Why, this very night, after I’d written the above and scheduled it to go live at 4 PM on Wednesday the 13th, we watched a 61 year old episode of To Tell the Truth. One of the impostors had a voice that sounded terribly familiar to us, but a face we didn’t recognize at all. When the game was over, he said his name was “Bobby Lloyd, and I’m a TV announcer at WHEC TV in Rochester, New York!” Two years later, he was Bob Lloyd, and he was on staff as an announcer for the ABC network, where he would say “Dark Shadows is a Dan Curtis production.”

No episode of Dark Shadows premiered 56 years ago this afternoon; the show was preempted by ABC-TV’s coverage of the Apollo 11 mission. That mission included the first steps taken by humans on the surface of the Moon, at a site 25 kilometers south of a crater then known as Sabine D. The following year, Sabine D was renamed Collins. That was not an attempt to console Dark Shadows fans for the trauma of a Monday spent away from Barnabas and his relatives, but was an honor given to United States Air Force officer Michael Collins, Command Module pilot on Apollo 11. Moreover, the nearby crater named Moltke was not named for Alexandra Moltke Isles, who played well-meaning governess Vicki in 333 episodes of Dark Shadows, but for her distant cousin Count Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, who died in 1891 and never appeared on the show (as far as we can tell.)

These changes to the map of the Moon remind me that, on this 56th anniversary watch-through, I’ve been revising my mental map of the show’s development. I used to divide it into chunks with labels like “Meet Vicki,” “Meet Matthew,” “Meet Laura,” “Meet Barnabas,” “Meet Julia,” “Meet Angelique,” and so on. In that scheme, this 161st week is an early part of the chunk I would have called “Meet Petofi.” I still see that the show defaults to having a main character, but now I think in terms of larger units. I also tend to focus more on the writing staff than on the central characters. So the first 38 weeks drew their vitality from the story of Vicki’s attempt to befriend strange and troubled boy David, a story which reached its conclusion at the end of the Phoenix tale, when David chose Vicki and life over his mother and death. That was Dark Shadows version 1.0, and I subdivide it less into the parts driven by Vicki, Matthew, and Laura than into the parts written by Art Wallace alone, by Wallace in alternation with Francis Swann, and by Ron Sproat and Malcolm Marmorstein with uncredited contributions by Joe Caldwell.

Dark Shadows 2.0 ran from March to November 1967, and its most interesting theme was vampire Barnabas Collins’ attempt to pass himself off as a living man native to the twentieth century. The first part of this, written by Sproat and Marmorstein, was even more slow-paced than were the first 38 weeks. Caldwell was credited with a number of scripts from May through October, Gordon Russell joined the staff in July, Marmorstein was fired in August, and Sam Hall replaced Caldwell in November. With each of those changes, the pace picked up and the overall quality of the scripts improved noticeably. There was also a shift in story in the middle of this period, as mad scientist Julia Hoffman teamed up with Barnabas in an attempt to physically transform him into a human, shifting his masquerade from an acting job to a medical problem.

Dark Shadows 3.0 ran from November 1967 to March 1968. This was a costume drama set in the 1790s, an era to which Vicki had traveled when she came unstuck in time while participating in a séance. It seemed at first that it would invert the 1967 story, with Vicki trying to pass herself off as a native in the time to which Barnabas actually belonged, but for some reason they chose to write Vicki as a screaming ninny during this segment. Mrs Isles made a valiant effort to overcome the painfully dumb lines she was given, but by the end of it, the character was no longer sustainable.

Barnabas was a human through the first half of Dark Shadows 3.0, and a vampire for the second half. That alternation answered three questions, each of which opened a door for further development.

First, the audience wanted to see how Barnabas became a bloodsucking ghoul. When they showed this happening in the course of his relationship with wicked witch Angelique, they laid the groundwork for more stories involving her.

Second, the audience wanted to see what Barnabas was like in his lifetime. When they showed this, they proved that he didn’t have to be a vampire to be interesting, and made it possible for Julia’s experiment or some other effort to free him of the effects of the curse to succeed.

Third, the audience wanted to see what Barnabas would be like if he were as deadly as one might expect a vampire to be. In the whole of 1967, Barnabas killed only two characters, each of them a middle aged man who had run out of story and seemed likely to disappear anyway. But he kills seven people in 1795-1796, not counting people who died of fright or confusion or despair as a result of seeing him.

When it was set in contemporary times, Dark Shadows was careful to keep its characters alive. They need to fill 22 minutes a day with conversations, and if they end up with Barnabas alone on the estate of Collinwood those will get to be rather one-sided. But since they were not committed to staying in the 1790s, they could let him slaughter people with abandon. That created a fast pace that the show tried to maintain for the rest of its time on the air. In consequence of that pace, by the end of the 1790s segment the show had left behind its origins as a Gothic romance appealing to an older demographic who were impressed that Joan Bennett was in the cast and had become a kids’ show.

Vicki returned to 1968 in #461, but Dark Shadows 3.0 did not end at that moment. Vicki came back to exactly the same collection of narrative dead-ends the show had gone to the eighteenth century to escape. It wasn’t until #466 that Barnabas found that he had been cured of vampirism- not by Julia, but by another mad scientist. That set the tone for Dark Shadows 4.0. Version 2.0 may have been content with one mad scientist, but 4.0 needed at least two, in addition to multiple witches, Frankensteins, vampires, ghosts, an invisible man, and, if not the Devil himself, at least one of the assistant managers of his upper New England operations. The fast pace of the 1790s segment turned into a frantic dash through this Monster Mash era.

In the course of Dark Shadows 4.0, there were four personnel changes that had especially profound effects. Two were in the cast. At the end of the segment, Mrs Isles left the role of Vicki, never to return to the show. Though Vicki had been pushed to the margins long before, she was so strongly associated with the first phase of Dark Shadows that every time she appeared on screen she made a connection with those early days. With her departure, that link is broken.

Thayer David, who had played crazed handyman Matthew Morgan in 1966 and much-put-upon indentured servant Ben Stokes in the 1790s segment, returned in 1968 as Ben’s descendant, occult expert Timothy Eliot Stokes. Ben was a commentary on Matthew, an example of what he might have been had he not grown up in a community under the somber mark of the Collinses and the many curses they bear. As such, David was like the rest of the cast for the 1790s, playing a character who shed light on the part he took in contemporary dress. But as Stokes, he is playing a man who has no direct connection to Matthew, and little connection to Ben. With that doubling, we see that any performer might return to the cast in a new role at any point in the story.

The other personnel changes during Dark Shadows 4.0 took place behind the camera. Ron Sproat ended his duties as a regular member of the writing staff late in that period, and left the show altogether shortly after. Sproat was the most devoted to conventional soapcraft of all the writers, and was the only one who consistently took care to keep the show comprehensible to first-time viewers. But he didn’t have an especially fertile imagination for story points or for clever dialogue. As Hall and Russell hit their stride and really started cooking, Sproat’s relative weakness became impossible to ignore. The show entered its most exciting phase when Sproat left, but his absence would later be felt at times when the staff tried to keep the story moving at a breakneck pace even when they were too fatigued to make sure it all made some kind of sense.

The least remarked of all the personnel changes was the departure of director John Sedwick. Sedwick was an outstanding visual artist, the equal of his colleague Lela Swift. Swift stayed with the show to the end, eventually combining the role of producer with responsibility for directing half the episodes. But after several men helmed a few episodes each, they settled on the lamentable Henry Kaplan as her alternate in the director’s chair. Kaplan was a famously poor director of actors, and the visual compositions he knew how to orchestrate ran the gamut from closeup to extreme closeup to even more extreme closeup. Dark Shadows was never all that easy for first-time viewers to take seriously, and when you tune in to one of Kaplan’s efforts you’re likely to dismiss it before you hear a word of dialogue.

As Dark Shadows 3.0 didn’t end until the show had already been back in 1968 for a week, so version 4.0 ended well before it began its next time travel story. In #627, we meet werewolf Chris Jennings and hear about Chris’ little sister, who will eventually be named Amy. Amy befriends David, and together they become the central figures in the Haunting of Collinwood by the ghost of Quentin Collins. This leads Barnabas to travel back in time to 1897 in #701. Barnabas and the show will stay in that year until #884. This whole arc, from #627 airing in November 1968 to #884 airing in November 1969, makes up Dark Shadows 5.0.

The major subdivisions of version 5.0 are the “Meet Amy” section that runs from #627 to #700, the “Meet Quentin” section from #701 to #778, and the “Meet Petofi” section from #778 to #884. The transitions among these segments showed that the shift from one time frame to another is not essential for making a chapter break in the show. The reset from the focus on Quentin to the focus on Petofi rolls across a few weeks, and does not have the single spectacular moment when we first find ourselves in 1897, but it is just as definite a break. It even involves doubling Thayer David, who played broad ethnic stereotype Sandor Rákóczi in 5.0.1 (the “Meet Quentin” section,) and who plays sorcerer Count Petofi in 5.0.2 (the “Meet Petofi” section.) As Ben was an alternative version of Matthew, so Petofi is an answer to the question “What would Stokes be like if he were evil?” As such, he brings version 5.0.2 in line with version 3.0, in which characters in one time frame mirror those in another.

That we can make a major transition without returning to the 1960s raises the question of whether we need to go back there at all. Barnabas is on a mission to save David and Amy and Chris, but he could always find a fresh threat to them in the 1890s. And the characters we have met in that period are at least as compelling as are those we left behind in the contemporary time frame. Despite the deficiencies of Henry Kaplan, the writing staff of Hall, Russell, and the brilliantly witty Violet Welles combine with an almost unanimously strong cast to make the dialogue glitter. It is the strongest period of the show by far, and it is difficult to imagine wanting it to end.

We will go back to a contemporary setting, eventually. The H. P. Lovecraft-inspired monster cult known as the “Leviathans” will be the center of version 6.0; in that segment, the show will start on the most adult tone it ever adopts, and end pitched squarely at a very young demographic. The change may well have come because the three-person writing staff burned out, and became a grave matter when Welles left the show.

Version 7.0 is another time travel story, but a story of traveling sideways in time, to an alternative universe where the characters wear clothing appropriate to 1970 but have different personalities and different relationships than do the people with the same names and faces whom we have met previously.

Version 8.0 is the most ambitious of all the segments, starting with a trip in time to the far-off future year 1995, returning to 1970 for a reprise of the Haunting of Collinwood, this time by a ghost who resembles Quentin in hairstyle and wardrobe but not in height, and proceeding to a long stay in the year 1840. That version had enough characters and enough story to last indefinitely, but Hall and Russell were the only full-time writers, and they simply could not keep it up. It finally collapsed, and the last nine weeks were set in another alternate universe, with no characters in common with the stories we had seen up to that point.

Version 9.0 had a drab feeling; some say it isn’t Dark Shadows at all, but another series shot on the same sets with some of the same actors. The name Dim Reflections has been proposed for it. There is one week in the middle of Dim Reflections when Violet Welles comes back to make some uncredited contributions to the scripts; you can tell it’s her, because all of a sudden the characters have senses of humor. But after that Gordon Russell is all alone at his typewriter until Sam Hall returns for the very last day, and by that time everyone knows it is time to go.

No episode of Dark Shadows debuted on ABC-TV 56 years ago today, since that was Christmas Day. So in place of an episode commentary, I’ll share a link to Smartphone Theatre’s 2022 production of “The Gift of the Magi,” starring Kathryn Leigh Scott and David Selby.

No episode of Dark Shadows premiered 56 years ago today. That was Thanksgiving, and ABC was showing football at 4 PM.

At this point, Alexandra Moltke Isles had left the part of well-meaning governess Victoria Winters, marking the last step in the character’s long decline from her original position as the show’s chief protagonist. Vicki spent her childhood in a foundling home where she was left as a newborn with a note reading “Her name is Victoria. I cannot take care of her.” During Dark Shadows‘ first months, Vicki was on a quest to find out who her parents were. The show hinted pretty heavily that her mother was reclusive matriarch Elizabeth Collins Stoddard and her father was someone other than Liz’ long-missing husband, the scoundrelly Paul Stoddard, but the whole thing was dropped without any real resolution long ago.

In yesterday’s episode, Frankenstein’s monster Adam was on his way to Vicki’s room, apparently meaning to kill her. We understand Adam’s violence too well to regard him as a very cold villain. Most of the harm he has done is the result of his not knowing his own strength, and the rest is the predictable consequence of the abominable education he has received from his creators, mad scientist Julia Hoffman and recovering vampire Barnabas Collins, and from suave warlock Nicholas Blair. To longtime viewers, Vicki has been important enough for long enough that we do not see any prospect that a character as sympathetic as he is will become her murderer. On the other hand, Nicholas has now left the show, and there is nowhere for Adam to go within any of the ongoing storylines. If he simply disappears, he will be another significant loose end.

In September 2023, I left a long comment on Danny Horn’s Dark Shadows Every Day describing a fanfic idea that would at one stroke answer the questions of Vicki’s origin and of Adam’s fate. Below is a lightly edited version of that comment:

Here’s an idea I had today for a story that would save Vicki.

It would be a TV movie airing late in 1969. Start with a prologue set in Collinwood at that time. Adam returns, looking for Barnabas and Julia. He’s very well-spoken and accomplished now, but still socially awkward, still prone to fits of anger, and in need of help to get papers that he needs to establish a legal identity.

He finds that Barnabas and Julia are gone. He also happens upon some mumbo-jumbo that dislocates him in time and space.

It plops him down in NYC in 1945. With his facial scars, everyone assumes he’s a returning GI injured in the war. He meets a young woman, supporting herself working at a magazine about handheld machines, trying to establish independence from her wealthy family back in Maine. This woman, played by Alexandra Moltke Isles, is Elizabeth Collins.

Adam and Elizabeth slide into a love affair. She has another boyfriend, a dashing young naval officer named Paul Stoddard (Ed Nelson.)

Elizabeth is frustrated with both Adam and Paul; Adam refuses to talk about his background, and while Paul says many words when asked about himself, he doesn’t really give significantly more information than Adam does. Paul is slick, charming, and familiar with all the most fashionable night spots, but he does show signs of a nasty side. Besides, he rooms with a disreputable young sailor named Jason McGuire (John Connell) who keeps turning up at the most disconcerting moments.

For his part, Adam is sincere, passionate, and attentive, but given to quick flashes of anger. He’s just as quick to apologize and sometimes blubbers like a giant baby with remorse for his harsh words, but he’s so big and so strong that when he is carried away in his fits of anger Elizabeth can’t help but be afraid of him. Besides, he’s not a lot of fun on a Saturday night. He doesn’t have a nickel to his name, and his idea of an exciting weekend is an impromptu seminar on Freud’s TOTEM AND TABOO, followed by a couple of games of chess.

Elizabeth’s mother (Joan Bennett) comes to town. Mrs Collins is appalled by Adam’s scars, impatient with his refusal to discuss his background, and contemptuous of his obvious poverty. Paul’s effortless charm and sparkling wit, packaged in the naval dress uniform he makes sure he’s wearing when she first sees him, fit far more tidily into her vision of a son-in-law. Mrs Collins presses her daughter to spurn Adam and pursue Paul, and for a time Elizabeth tries to comply with her wishes.

Yet she cannot forget Adam. Paul realizes this, and sees his chance at an easy life slipping away. We see him in a dive in Greenwich Village telling Jason McGuire that Elizabeth and her inheritance are going to end up with the scar-faced scholar. He and McGuire review Adam’s weaknesses, and decide they can exploit Elizabeth’s concern about his temper. They trick her into believing that Adam is on the run from the law, having beaten his wife to death. They lead her to believe that it’s just a matter of time before his occasional verbal outbursts give way to physical abuse, and that when that happens it will be too late- he will kill her. Believing this, Elizabeth gives Paul another chance, but still cannot break things off with Adam.

Adam does not know what Paul and Jason have led Elizabeth to believe. He knows only that she has become distant from him, and that she is still seeing Paul. He becomes angry and shouts at Elizabeth. He reaches for an object; she believes it is a blunt instrument with which he will kill her. In a moment of panic, she grabs a gun she has been studying for an article the magazine has assigned her to write and shoots him. As he lies motionless on her floor, she discovers that he wasn’t reaching for a weapon at all- he was reaching for a love letter that he had written to her. She realizes that he was no threat to her, that she has shot him for no reason.

She flees to Paul and Jason’s apartment, telling them that she has killed Adam. Paul calms her and promises to take care of matters so that she will not be suspected of any crime. Paul and Jason go to her apartment and find it empty. There are bloodstains on the carpet where Adam fell, and a trail of bloodstains leading down the hallway out the front door. They follow the stains and find Adam nursing a serious, but clearly not fatal, wound. They lead Adam back to Elizabeth’s apartment. They draw on their naval training to remove the bullet, clean and dress the wound. After a conversation. Adam admits that there is no point in his pursuing Elizabeth, and he agrees to leave town. Paul gives Adam some money and promises to tell Elizabeth that he is all right and that he doesn’t hold a grudge. Adam shakes Paul’s hand and leaves.

Paul and Jason clean the bloodstains. They then return to their own apartment. On the way they exchange a look that begins as nervous, and ends with two broad grins. Elizabeth asks why they were away so long. They tell her that it takes quite a while to dispose of a corpse. She sobs. Paul holds her.

Paul and Elizabeth announce their engagement. A few weeks later, the doctor informs Elizabeth that she is pregnant. The child must be Adam’s. Paul is not interested in raising any child, and certainly not interested in splitting the estate with a child not even his own. He orders Elizabeth to give the baby up. She refuses. He points out that she wouldn’t be able to do much mothering if she were in prison for murder. She sobs. In the final scene, we see Elizabeth outside on a snowy day, holding a basket and writing a note. In voiceover, we hear the contents of the note: “Her name is Victoria. I cannot take care of her.”

Episode 509 of Dark Shadows did not air on ABC-TV as scheduled on 6 June 1968. The network instead broadcast news coverage related to the assassination of US Senator Robert F. Kennedy.

At this point, one of Dark Shadows’ storylines was a loose adaptation of Frankenstein. Five years later, Dan Curtis, the show’s executive producer, would bring another adaptation of the novel to the small screen, as part of ABC-TV’s late night programming that ran under the umbrella title Wide World of Mystery.

Originally presented in two parts, each filling a 90 minute window, Dan Curtis’ Frankenstein is now available on Tubi in a 2 hour, 6 minute cut. It is more faithful to Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s original novel than were any previous adaptations, a point Curtis frequently made.

The main theme is made clear in the opening. Dr Victor Frankenstein is supposed to give a talk to a classroom of students in white coats, but they keep shouting him down. The professor identifies Frankenstein* as the winner of an academic prize and urges his unruly pupils to give him a hearing. That gets Frankenstein enough time to tell the class that they don’t understand what he has been saying, to make a little speech about the scientist’s obligation to create a superhuman life form in the laboratory, and to look frustrated when they walk out on him. The professor stays behind and tries to reason with Frankenstein, who doesn’t seem to be listening to a word he says.

No communication occurs in that scene, and very little occurs in any scene that follows. That’s a natural basis for a drama about the Frankenstein story. The mad scientist is disconnected from any voices of sanity, and the being he creates does not initially understand any language and has no frame of reference in common with anyone he might meet.

Frankenstein goes to his laboratory, where his friends Hugo and Otto are wearing funny hats and preparing to celebrate the prize he won. Hugo and Otto quickly gather that Frankenstein is uninterested in a party, but the heavy, ominous music on the soundtrack** tells us that more is going on in Frankenstein’s mind than his friends know.

Frankenstein insists that the experiment go on, an idea Otto resists. Otto wants to stop “while there is still time”; Frankenstein says that they have already passed the time when stopping was possible. Frankenstein seems to be talking about the danger that the body they have assembled will decompose, while Otto seems to be talking about the consequences of continuing to forage for organs and of bringing the body to life. Again, neither man reaches the other.

Frankenstein, Hugo, and Otto go shopping in the graveyard, where the caretaker shoots Hugo. Frankenstein and Otto get Hugo back to the laboratory. Frankenstein wants to call for help, even if it means prison, but Hugo insists that he and Otto use his heart to complete the experiment. He dies. Frankenstein decides to honor his wish. They will tell people that Hugo went climbing in the mountains, and after a while searching for his body people will simply give up. So Frankenstein and Otto will tell a false story, on the basis of which people will make and follow pointless plans. They then prepare to complete the experiment.

The preparations are interrupted when unexpected visitors arrive. They are Alphonse, father of Frankenstein; Elizabeth, fiancé of Frankenstein; and Henry, brother of Elizabeth and friend of Frankenstein. Frankenstein greets them, flustered, and says that they have come at a bad time and must stay at the inn. Alphonse and Henry wonder why Frankenstein did not receive Elizabeth’s note informing him of the date of their arrival; Elizabeth sees the note, unopened, on a table. Yet again, the emphasis is on a lack of communication.

Frankenstein and Otto resume the experiment. After a long display of flashing sparks, they cannot get any vital signs from the body. Frankenstein declares that the experiment has failed and orders Otto to burn “all the books, every journal!” They are out of the room when the body starts to move. Frankenstein comes in by himself, sees what’s happening, and says, in a voice too quiet to be heard outside the door, “He’s alive.” This unheard “He’s alive” is an obvious contrast with Colin Clive’s manic cry of “It’s alive!” in the 1931 film, emphasizing that while Clive’s Frankenstein may have been alienated from others by his obsessions, Robert Foxworth’s is simply unintelligible to the people he knows. The aftermath of the experiment is a recreation of the equivalent scene in episode 490 of Dark Shadows, but the idea of destroying the records of the experiment is added to show that Frankenstein is fighting against communication as such.

Once Frankenstein and Otto realize that the big guy has come to life, they help him up off the table. The experimenters handle their creation with a gentleness and good cheer that makes a striking contrast with the extreme callousness patchwork man Adam received from his self-pitying creators in Dark Shadows, and comes at a moment when both the immediate aftermath of the experiment and John Karlen’s presence as Otto have brought that story to the forefront of our minds.

Frankenstein and Otto are surprised that the big guy doesn’t have the memories of the professor whose brain they implanted in his head. Frankenstein speculates that the electric shocks they used to animate him may have wiped out his memories, but also thinks that those memories might eventually come back. Their attempts to communicate with him, therefore, are based not so much on listening as on an effort to conjure up the late Professor Lichtman. Still, Frankenstein is happy to note that the big guy has the reactions, not of a newborn, but of a four year old.

Frankenstein leaves Otto alone with the big guy while he goes off to placate his father, Elizabeth, and Henry. Otto teaches the big guy to play catch. Delighted with this, the big guy hugs Otto. He doesn’t know his own strength, nor does he understand what Otto means when he gasps out “Stop!” When Frankenstein comes back to the lab, he finds the big guy standing over Otto’s corpse, pleading “Play, Ot-ta, play!”

Frankenstein takes out a pistol, but cannot bring himself to kill the big guy. Instead, he orders him to get back on the table. He readily complies, and Frankenstein straps him in place. He takes Otto’s body from the lab. As soon as Frankenstein has left the room, the big guy easily breaks the straps and goes to the door. Finding it locked, he smashes some lab equipment.

Frankenstein takes Otto’s body to his room above what appears to be a tavern. He sets up Otto’s telescope by an open window and drops his body to the ground. By the time he returns to the lab, the big guy is gone.

The big guy wanders about and has some poignant moments when children see him and react with fear. He makes his way to a house occupied by the de Laceys, a blind girl named Agatha and her elderly father. He hides unnoticed in a closet there for, apparently, several months. Shortly after he takes up residence, Agatha’ brother, a sailor, drops his fiancée off at the house. She speaks only Spanish, and Agatha and her father speak only the language of Ingolstadt, which in this movie is identified explicitly as “inglés,” even though Ingolstadt is in Germany. In one of the first English lessons Agatha gives her sister-in-law to be, she says that the storm outside is “a summer rain”; in a later scene, while the big guy is still undetected in the closet, she mentions that October is almost over. Both the dramatized difficulties of language teaching and the unremarked failure of Agatha and her family to detect a huge man crouching a few feet away from them for so long stress the theme of non-communication.

The big guy makes a crude doll and talks to it while Agatha gives her sister-in-law English lessons. He speaks quietly, but not so quietly that it isn’t absurd that they fail to notice him. I suspect that absurdity is as intentional as is the doll’s inability to talk back.

One autumn night, the big guy comes out of his closet and walks around the vacant living room. He starts talking. He maintains a warm smile throughout, uses sophisticated grammatical constructions and a wide variety of phrases, and acts out a scene full of pleasantries, apologizing for the roughness of his manner and explaining that he has known little kindness from people. He catches a glimpse of himself in a mirror, the first time he has seen such a thing. He recoils from his face, and exclaims “Ugly!”

In the morning, he goes outside and knocks on the front door. When Agatha enters, he tells her he is “a friend you do not know.” She is puzzled by this expression, but lets him in anyway. She jumps to the conclusion that he is a traveler; he tells her that he wishes the whole world were blind. He may have become capable of speech, but now he is terrified of nonverbal communication. The conversation goes quite well until she wants to touch his face. He refuses. She insists, and chases him around the room. At that moment, her father, brother, and sister-in-law to be enter. Misunderstanding, they jump to the conclusion that the big guy is the one chasing Agatha. They fight him, and he injures her brother.

Mr de Lacey, with Agatha and his daughter-in-law to be in tow, brings the injured young man to Frankenstein’s house. When Frankenstein hears their description of the big guy, he mutters a few words about how to tend the patient’s wounds, and sets out with a gun to hunt his creation. They are bewildered that the doctor has rushed off after giving them so little information, and Elizabeth is left to try to smooth things over with them.

That night, Frankenstein catches a glimpse of the big guy and shoots him in the forearm. The big guy gets away. He has no idea who Frankenstein is or why he would shoot him. He finds himself on the grounds of Frankenstein’s house. Frankenstein’s little brother William is outside. They meet at the fountain there. William is unafraid of the big guy and makes a tourniquet to stop the bleeding from his gunshot wound. The big guy and William are quite happy together until William sees Elizabeth and decides to call her over. The big guy tells him not to call anyone, but William ignores him. Panicked, the big guy covers William’s mouth. He still doesn’t know his own strength, so he accidentally breaks William’s neck, killing him instantly. Unlike with Otto, the big guy now knows what he has done, and so his plea is not “Play!” but “Don’t be dead!”

Frankenstein finds William and realizes what has happened. He resumes his hunt. When he finds the big guy, he fails to kill him. The big guy asks Frankenstein who he is and why he hates him. Frankenstein explains enough to draw the big guy’s full rage. He is furious that he was created to be alone, and complains that “I don’t even have a name.” He insists that Frankenstein create a mate for him. When Frankenstein demurs, the big guy threatens to kill everyone who crosses his path. This again echoes Dark Shadows, where Adam insisted that Barnabas and Julia build a “Friend” for him and responded to their protests with a similar threat. Unlike Adam, who was put up to demanding a bride by warlock Nicholas Blair and who didn’t appear to have any idea what sex was, the big guy has seen Frankenstein and Elizabeth together and says that he wants what Frankenstein has.

Frankenstein tries to comply with the big guy’s demand. He has built a womanly body, put it on his table, and hooked it up to wires that will conduct the charges from an electrical storm raging outside. Henry, furious that Frankenstein has paid so little attention to his sister, barges into the lab and sees the body of the Bride. Before he can tell anyone about it, the big guy kills him.

Frankenstein tries to complete the experiment. The big guy lets himself in and watches as the lightning makes the Bride arch her back, open her eyes, and scream. This is far more activity than the big guy showed before Frankenstein and Otto disconnected him, but Frankenstein leaves the Bride hooked up while the electric charges surge into her. She dies on the table. The big guy says that Frankenstein deliberately killed her. He doesn’t bother to deny it, but says that his conscience wouldn’t let him repeat the misdeed he committed in bringing the big guy to life. At that, the big guy vows to stalk Frankenstein for the rest of his life. He tells him that he will be there on his wedding night.

Frankenstein finally tells Elizabeth the truth. She resolves to stick with him regardless. They leave town. They check into an inn, where the innkeeper brings his friend the Burgomaster over to perform a wedding ceremony. The innkeeper and the Burgomaster explain that Frankenstein must go across the square to sign the registry to make the marriage legal. For some reason Elizabeth must remain in the room by herself while he does this. He resists, but Elizabeth and the Burgomaster insist it will be all right. Of course Elizabeth is dead when Frankenstein returns to the room a few minutes later.

Once more Frankenstein takes his gun to hunt the big guy; once more he fails to kill him. This time the big guy kills him. Frankenstein winds up dying cradled in the big guy’s arms, in a Pietà pose, while the big guy expresses his remorse for his killings. He speaks of “the pain I felt when I killed little William, the hate I felt for myself when I left Elizabeth dead,” and begs Frankenstein not to die. He does anyway, and the big guy walks off, encountering some policemen who shoot him to death.

For a quarter century before this movie was made, feature films had spent a great deal of time exploring non-communication. Filmmakers like Michelangelo Antonioni, Jean-Luc Godard, and above all Alain Resnais had made dozens of movies about people who simply could not get through to each other. The result was a pervasive sense of tentativeness, as potential relationships were outlined but could not develop and potential events were envisioned but could not occur. The same tentativeness dominates this movie.

*Throughout the movie, people call the scientist “Frankenstein,” while his creation is known only as “The Giant.”

**Recycled from Dark Shadows and other collaborations between Curtis and composer Robert Cobert, as is nearly all the music.

It used to be customary in many parts of the English-speaking world to tell ghost stories at Christmas. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is today the most famous of these stories, and it was dramatized in 2021 by the surviving members of the Dark Shadows cast.

But there are many others. John Kendrick Bangs’ “Water Ghost of Harrowby Hall” is one. Here is a recording of Jonathan Frid’s dramatic reading of it. He did it in the fall of 1969, and it was posted to YouTube by Frid’s close friend and longtime business partner Mary O’Leary in 2022.

The story echoes Dark Shadows at several points, most obviously when we hear about a ghost which, like that of Bill Malloy in #85, leaves pieces of the sea in its wake, and when we hear about a maiden who, like so many in the series, jumps off a seaside cliff and finds a watery grave at its foot.

When we listened to it, my reaction prompted my wife, Mrs Acilius, to say that I was “trying to ruin it, like you always do.” I’d pointed out that the Oglethorpes spend the whole story trying to build structures to contain the water that the ghost brings with her. Surely the logical thing would be to build a drain to sluice it all out of the house.

When Mrs A said that this would leave them without a story to tell, I protested that it should give them a more interesting story. Let them make a series of unsuccessful attempts to keep the water out, then an unsuccessful attempt to keep it in, and finally construct a means of draining it out. That would set you up for an ending where you see that the drainage, even though it might be mechanically successful, will still be an unsatisfactory response to the real problem, which is not the water at all but the curse of which the water is a symptom. That led her to agree that I was not “trying to ruin it,” which is about all I could hope for, I suppose.

As I’ve gone along making these notes, I’ve occasionally been moved to tag episodes as “Genuinely Good” or “Stinkers.” Since no episode of Dark Shadows aired 56 years ago today- 23 November 1967 was Thanksgiving Day in the United States, so ABC showed football games instead of its regular programming- I’m taking the opportunity to list the installments to which I gave these labels.

Genuinely Good Episodes

#25. Written by Art Wallace. Vicki finds an incriminating piece of evidence in David’s room.

#32. Written by Art Wallace. Roger and Liz face the fact that it was David who tried to kill Roger.

#50. Written by Art Wallace. Vicki and Carolyn see Bill Malloy’s body below the cliff.

#59. Written by Art Wallace. The sheriff comes to Collinwood and questions Roger.

#68. Written by Francis Swann. Roger encourages David to murder Vicki.

#69. Written by Francis Swann. Mrs Johnson visits Burke in his hotel room.

#87. Written by Francis Swann. Roger finds Vicki in the sealed room and releases her.

#102. Written by Francis Swann. David has a conversation with the portrait of Josette.

#103. Written by Francis Swann. Vicki and Burke investigate Roger.

#112. Written by Ron Sproat. Liz rescues Vicki from Matthew.

#126. Written by Ron Sproat. The ghosts of Josette and the Widows, accompanied by that of Bill Malloy, rescue Vicki from Matthew.

#146. Written by Malcolm Marmorstein. Sam burns his hands.

#182. Written by Ron Sproat. Roger begins to suspect that Laura might really be a supernatural being and a threat to David.

#253. Written by Joe Caldwell. Maggie gives Willie her ring. The first really good episode of Dark Shadows 2.0.

#254. Written by Joe Caldwell. Carolyn and Buzz announce their engagement.

#258. Written by Malcolm Marmorstein. Maggie talks with Sarah.

#260. Written by Ron Sproat. Maggie escapes from Barnabas.

#265. Written by Malcolm Marmorstein. First appearance of Dr Julia Hoffman.

#318. Written by Gordon Russell. Barnabas and Julia hide in the secret room of the mausoleum while Sam and Woodard search the outer part.

#325. Written by Gordon Russell. Sarah comes to David in a dream.

#327. Written by Gordon Russell. David communicates with two aspects of Sarah that don’t communicate with each other.

#333. Written by Ron Sproat. Burke and Woodard search Barnabas’ basement.

#344. Written by Joe Caldwell. David knows what’s going on and has given up hope of changing it.

#345. Written by Gordon Russell. Burke is missing and feared dead.

#348. Written by Joe Caldwell. Julia tries to save the experiment. The first episode of Dark Shadows to fully integrate color into a coherent visual strategy, and probably the best episode of the series up to this point.

#351. Written by Gordon Russell. Barnabas adds Carolyn to his diet.

#363. Written by Gordon Russell. Tony catches Carolyn going through his safe, then Sarah appears to Barnabas.

#364. Written by Gordon Russell. Sarah confronts Barnabas.

#365. Written by Sam Hall. A séance at Collinwood has an unexpected result. This is the final episode of Dark Shadows 2.0.

I credit the writers, because there were only two directors in this period of Dark Shadows, Lela Swift and John Sedwick, and they didn’t differ sharply in approach. The rest of the production staff was the same in every episode, so the writers were the only ones whose names seemed like they might give a clue as to what set the best episodes apart from the worst ones.

I’m very surprised to see Marmorstein’s name in this list three times. Joe Caldwell was making uncredited contributions to the writing from #123 on; #146 is very much in his style, and I suspect he was its true author. But Caldwell was getting on-screen credit by the time of #258 and #265, so I think those must actually have been Marmorstein’s handiwork. Granted, neither of them is all that close to the top of the all-time great list, and the actors and directors do a lot to elevate them. Even so, they do prove that Marmorstein was not the total incompetent he so often seemed to be.

One thing I notice is that many of these episodes feature long-delayed confrontations in which the character learns information they hadn’t expected and can’t use right away. So in #25, David talks with Vicki and for the first time makes an explicit statement about his father’s accident, while Liz talks with Roger and for the first time makes an explicit statement about Vicki’s origins. In each case, the explicit statement is an obvious lie and the person telling it demands that the other go along with it. Hearing the characters talk about issues they’ve been evading for a long time relieves some worn-out suspense, while the actual content of the conversation builds fresh suspense as we wonder what use Vicki and Roger will make of the knowledge that David and Liz are lying. And of course the similarity between David’s behavior and his aunt’s shows that the boy is carrying on a family tradition.

In #32, Roger and Liz finally admit to themselves and each other the fact that David caused the accident. While they set to work covering this up, Roger tells Liz that he isn’t sure David really is his son. Liz refuses to entertain the question, but it sets us up for the storyline centering on David’s mother Laura.

Jumping ahead to #258, the conversation between Maggie and Sarah shows that Sarah is able to interact with the living and suggests that she wishes Maggie well, but is just as inconclusive as were the conversations in #25 and #32. Sarah’s conversation with Barnabas in #364 shows that she is angry with him and trying to rein him in, but also shows that she has little direct influence over him.

Stinkers

#223. Written by Ron Sproat. David runs around and screams.

#249. Written by Ron Sproat. The family looks in the locked room and doesn’t find anything.

#266. Written by Ron Sproat. Liz is depressed.

#268. Written by Ron Sproat. Liz is still depressed.

#272. Written by Joe Caldwell. Liz has revealed her secret, and no one knows what to do about it.

#298. Written by Ron Sproat. It seems as if Maggie is going to remember what Barnabas did to her, but then she doesn’t.

#299. Written by Ron Sproat. It seems as if Barnabas is going to bite Vicki, but then he doesn’t.

#356. Written by Gordon Russell. Julia sticks her notebook in the clock, giving the clock the star turn it has been waiting for.

I suppose the first thing you’ll notice is that I didn’t come up with the “Stinkers” label until after Barnabas joined the show. If I’d thought of it sooner, Malcolm Marmorstein’s name would have graced the list many times. Also, there probably would have been some episodes there that aired on Fridays, as they didn’t really start to make an effort to do anything special at the end of the week until about halfway through Laura’s arc.

But I’m not going to go back and add the label to episodes from the first 42 weeks. I didn’t have any particular thought of making “Best” and “Worst” lists when I put them on; I was just marking some of my posts as raves or pans. So I’d be imposing a false organization on them if I went back through and did that.