A MacGuffin day today, as everyone is busy trying to get hold of the magical Hand of Count Petofi. Broad ethnic stereotype Magda Rákóczi stole the Hand, which incidentally is a literal severed hand, from Romani chieftain/ organized crime boss King Johnny Romana. She hoped to use it to cure handsome rake Quentin Collins of the werewolf curse she placed on him, but found that she was unable to master its powers. Several people have stolen it from each other since then; at the beginning of the episode it is in the possession of wicked witch Angelique, who is also unable to figure out how to use it to solve Quentin’s problem.

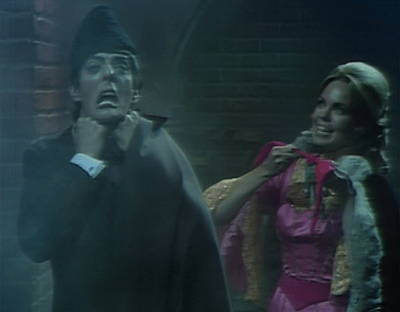

Today, a man named Aristide is holding Quentin prisoner. He straps Quentin to a table under a descending pendulum with what we are supposed to imagine is a razor sharp blade. He goes to Angelique and tells her that Quentin will die in minutes unless she gives him the hand. Since Angelique can’t see Quentin and Aristide doesn’t even describe the predicament, it isn’t clear why Aristide went to all this trouble, but it does create a memorable image and a nice homage to the works of Edgar Allan Poe. It would also warm the hearts of viewers mourning the end of the Batman TV series.

Meanwhile, a small and pretty young woman named Julianka has told Quentin’s distant cousin Barnabas Collins that she can cure Quentin if she has the Hand. He gets it from Angelique and takes it back to his house, where Julianka is waiting. She pulls a knife on him and declares that she is an emissary of King Johnny. She will not cure Quentin, and will stab Barnabas if he does not surrender the Hand. Barnabas calmly offers her money and the Hand if she will cure Quentin before she goes, but she refuses. He gives her the Hand. After she goes, we hear his thoughts as he is feeling sorry for her.

In the woods, Julianka hears a squeaking bat. She reacts with horror as the bat turns into Barnabas in front of her. She asks what he is; he tells her that he believes she knows what he is. He does not bite her, but she does become docile. It seems that Barnabas is using the “Look into my eyes!” vampiric power that he only recently acquired. It also seems that, while Julianka was lying when she originally claimed she had come to Collinwood to cure Quentin, she was telling the truth when she said that she was able to do so.

The Hand recently disfigured Quentin’s face, as it had a few days before disfigured the face of Quentin’s onetime friend Evan Hanley. Evan’s good looks returned after a while, and we have not been told why. Today Quentin’s do as well, and when he asks Aristide for an explanation the best he can do is to suggest it may just be luck. They spent quite a bit of time showing Evan’s efforts to cure himself, and even more time showing Quentin feeling sorry for himself, so this is not at all a satisfactory payoff.

In an original cast panel at a Dark Shadows convention in the 80s or 90s, David Selby reminisced about today’s scene between Quentin and Aristede. He said that when the cameras started rolling, he knew what actions he and Michael Stroka were supposed to perform, that he was supposed to end up tied to the table, and that it was supposed to take a certain number of minutes and seconds. He also knew that there was some dialogue they were to speak in the midst of all that, but he couldn’t remember any of it. The teleprompter was out of view. He looked at Stroka, hoping to see something in his face to jog his memory, and what he actually saw was the same blankness he was himself experiencing. So the two of them improvised their way through it. When they were done, they looked at the clock and saw that they had filled exactly the allotted time. But not a word of what they said was in the script. The resulting scene includes some awkward lines, but it has a great energy to it, just the sort of thing that gets you hooked on live theater.