Mad scientist Julia Hoffman has traveled back in time to the year 1897 to help her friend, vampire Barnabas Collins. Julia has fallen into the clutches of sorcerer Count Petofi and is bound and gagged in Petofi’s lair. A loaded revolver is tied to the doorknob, rigged to fire a round through her heart when the door opens.

Barnabas has learned where Julia is, but not about the death-trap in which she is ensconced. He storms into the building, turns the doorknob, and thereby discharges the gun. He sees Julia slumped over in her chair, and shouts at Petofi’s henchman that he will kill him. He then goes to Julia and finds that she is alive. There is a bullet-hole through the back of her chair, but she herself is unharmed.

Julia declares that there is only one explanation for this phenomenon that makes sense. Considering the kinds of stories that play out on Dark Shadows, we would think that an explanation that makes sense would be the one we could discard immediately, but Julia plows ahead. When she traveled back in time, only her “astral body” made the trip. Her physical body is still in 1969. For his part, Barnabas had a body in 1897, trapped in a sealed coffin. That body is hosting his personality, which is why he is subject to physical injury. But Julia is in no danger. When she later says that she can disregard Petofi’s threats, Barnabas says that if he finds out the truth, Petofi will just find another way to immobilize her, so she has to lie low.

Petofi is so powerful that Barnabas does not believe that he and Julia can fight him by themselves. So he tells Julia to summon wicked witch Angelique. Barnabas and Angelique have been enemies for centuries, but he thinks they have a common cause now. Angelique is determined to marry his cousin Quentin, whom he has befriended and Petofi has enslaved. So Barnabas expects she will agree to help fight Petofi.

Angelique does come in response to Julia’s message. She remembers Julia from time she herself spent in the 1960s, and is shocked to find her in 1897. Julia refuses to explain how she made her way back in time. She says that if Angelique can come to 1897 from 1968, she oughtn’t to be surprised she has come there from 1969. Angelique responds that Julia is not like herself and Barnabas. “I’m human,” says Julia. Since she is separated from her proper body, she isn’t fully human, not at the moment, but she still takes evident satisfaction in applying the label to herself. This marks a contrast with Angelique, who was offended earlier in the episode when Petofi laughed and taunted her for being “so human.” Julia and Angelique then snipe at each other about their respective relationships to Barnabas.

Julia says that it is essential Barnabas should “complete his mission” and solve the problems they were facing in 1969. Angelique responds that he will never be able to do that, because he has changed history too much in the time he has spent in 1897. This remark is intriguing for regular viewers. Barnabas’ six months of bungling around, picking fights, and committing murders must have had major consequences for what came after. That gives the show two ways forward. When Barnabas and Julia go back to a contemporary setting, they might meet an entirely different cast of characters and have to find a place for themselves in an alternate universe. Or they might do what they did when the show’s first time-travel story ended in March 1968, and dramatize the force of the Collins family’s propensity for denial. The head of the family in the 1790s decided to compel everyone in and around the village of Collinsport to pretend that none of the events we had seen had ever taken place, and when the costume drama segment ended we found that he had made that pretense stick ever since.

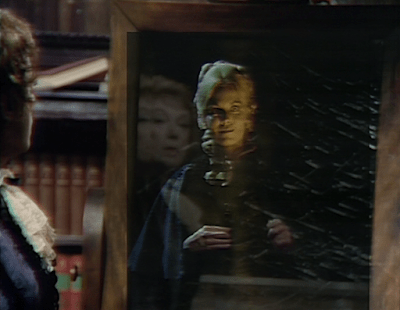

After Julia points out that it is to her advantage to emancipate Quentin from his bondage to Petofi, Angelique agrees to help. She still will not answer Julia’s questions. After she leaves the room, Julia looks in the mirror, sees an image of Angelique, and says that now she understands what she is going to do and believes it will work. That puts her one up on the audience.

The scene pairs Julia and Angelique as two women whose lives have been shaped by their pursuit of Barnabas. Their bickering makes this similarity explicit. When Julia looks in the mirror and sees Angelique, they put very heavy emphasis on the similarity. In a brilliant, but now inaccessible, post on the great Collinsport Historical Society,* Wallace McBride wrote that “On Dark Shadows, your reflection always tells the truth.” He demonstrated that on the show, reflections are very strongly coded as true, so much so that they must be making a serious statement when they give us an image like this one. They are committing to the idea that Julia is, in some important way, the same as Angelique.

There are also a couple of scenes featuring the repulsive Roger Davis as artist Charles Delaware Tate. Mr Davis is especially hard to take in a scene with Donna McKechnie as the mysterious Amanda Harris. Miss McKechnie had already done outstanding work on Broadway as a singer and dancer by this time, but she felt herself to be a beginner as an actress, and she could not conceal her discomfort when Mr Davis shouted his lines. The 4:3 aspect ratio of old-time American television meant that the performers spent much of their time only a few inches from each other, and when Mr Davis yells in Miss McKechnie’s ear, she winces. He clutches at her arm, and she recoils; before she can relax from that invasion of her space, he slams down on a table, making a loud noise and causing her to jump.

Mr Davis’ incessant shouting will bring back memories for viewers who have been with the show from the beginning. The scene takes place on a set which is known in the parts of Dark Shadows set in the 1960s as the Evans Cottage. The Evans Cottage was home to drunken sad-sack Sam Evans and his daughter Maggie, The Nicest Girl in Town. Sam, like Tate, was an artist, and the artworks scattered around the set in the 1897 segment remind us of the cottage’s iconography.

The first seven times we saw Sam, between #5 and #22, he was played by an actor called Mark Allen. Like Mr Davis, Allen had considerable training as an actor and a long resume of stage and screen appearances. Also like him, he is just terrible. Mr Davis did have extensive skills and could on occasion give nuanced performances, though he rarely chose to do so. He much preferred spending his time roughing up the women and children in the cast.

But Allen never once did a good job of acting. In each of his episodes, he either shouted every line with the same ear-splitting bellow, or whined every line in the same putrid snivel. Allen didn’t assault his scene partners on camera, as Mr Davis routinely did, though Kathryn Leigh Scott, who played Maggie, has made it clear that she did not feel safe in scenes where they embraced. Moreover, in some corners of fandom there are persistent rumors about abusive behavior off-camera that led to Allen’s dismissal. People claim to have heard remarks cast members and others associated with the show let drop at Dark Shadows conventions over the years, and from those remarks they come to some alarming conclusions about what Allen did behind the scenes. Who knows if those conclusions are correct, or if the people who report the remarks even heard them clearly, but Allen was so unpleasant as a screen presence that it is tempting to believe the worst about him.

The point of Tate’s scene with Amanda is that she does not want to believe that she is an artificial being who came to life when he painted a portrait that looked like her. Tate’s success as an artist is the result of magic powers Petofi gave him; he just recently learned that he can make things pop into existence by drawing or painting them. To convince Amanda that he has this power, Tate sketches an imaginary man. She screams, and we see her looking at the man who has come into being.

This seems like a bad choice on Tate’s part. Why not draw an inanimate object instead? If he’d drawn a hat or a gold bar or a gemstone, he could just have given it to Amanda with his compliments. But now he has a 25 year old man whom he is obligated to help make his way in the world. If an inanimate object wasn’t a striking enough image to send the episode out with a dash of spectacle, then Tate could have created a farm animal, such as a donkey or a goat. If Amanda didn’t want such an animal, Tate could just shoo it outside and be confident someone would claim it- Collinsport is supposed to be a tiny town in the middle of a rural area, after all. But for all the irresponsible behavior we’ve come to accept from characters on Dark Shadows, we are not going to be able simply to forget about this human being. They are going to have to do something to account for him.

*A site which has now been taken over by a “crypto-based casino” outfit! You’d be safer at Collinwood.