In #701, old world gentleman Barnabas Collins traveled in time from 1969 to 1897. For the next eight months, ending in #884, Dark Shadows was a costume drama set in that year. On his way back to a contemporary setting, Barnabas took a detour to the 1790s, when he was a vampire. Before he left the 1790s, he was abducted by and absorbed into a cult that serves supernatural beings known as the Leviathans. At their behest, he took a small wooden box with him to November, 1969, and functioned as one of the leaders of the Leviathan cult in that period.

The first six weeks of the Leviathan story has had its strengths. Ever since Barnabas was first cured of vampirism in March 1969, he has been under the impression that he was a good guy and has been doing battle with various supernatural menaces. He was hopelessly inept at this, and created as much work for the other characters by his attempts at virtue as he formerly did in his unyielding evil. That has made him a tremendously productive member of the cast, but it does leave him with a tendency to seem harmless, even when he is trying to murder his way out of a problem. But Barnabas the Leviathan chief has been ice-cold and formidably efficient. Even though not much has yet been done to hurt anyone, seeing him in this mode adds a note of terror to the proceedings.

Moreover, the Leviathans have voided Barnabas’ friendship with mad scientist Julia Hoffman. Since the relationship between the two of them has been the heart of the show for over two years now, from the hostility of their early days to the close bond they formed in the summer of 1968, this reinvigorates the action. It is as interesting to see them fight with each other as it is to see them collaborate against a common foe, and their hate scenes gain an extra depth because we keep wondering about their eventual reconciliation. If they play their cards right, they should be able to keep this up for months.

Today, it all falls apart. Barnabas has drawn a huge following of very young fans who run home from elementary school to watch the show. The 1897 segment was a triumph in large part because it had a core of stories that could hold the attention of adults while also appealing to the preteen demographic. But the Leviathan arc has so far had little to offer anyone but grownups. Apparently the kids were writing angry letters, because this episode, rushed into production at the last minute and bearing signs of haste in every shot, turns Barnabas back into the would-be hero who was such a klutz that he couldn’t even stay in the right century.

The creature who emerged from the box Barnabas brought from the past now appears to be a 13 year old boy and answers to the name Michael. In the opening scene, Michael orders Barnabas to kill Julia. Barnabas declares that he will not, and goes home. There, he tells his troubles to the box, then falls asleep in his chair.

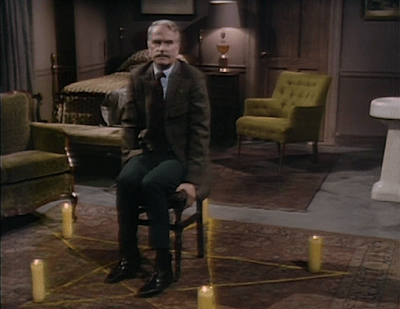

A hooded figure appears to him. This hooded figure says that he is a Leviathan, and tells Barnabas he must comply with Michael’s commands. The Leviathan is not named in the dialogue and there are no actors’ credits at the end, but reference works based on the original paperwork call him Adlar.

Adlar sets out to explain Barnabas’ position, much as Marley’s ghost did to Scrooge in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. The shortened production schedule shows in inconsistencies that litter Adlar’s speeches. At one point he says that the Leviathans needed Barnabas to transport the box from the eighteenth century to the twentieth; at another, he claims that they are holding his lost love Josette prisoner in the eighteenth century and will inflict a new, far more horrible death on her than the one she died the last time Barnabas was in the 1790s, a threat they will be able to carry out only if they have their own means of traveling back and forth through the years. Barnabas doesn’t pick up on this or any of Adlar’s other inconsistencies; perhaps he is too distracted by the many jump cuts that make this episode look like the videotape was edited with a rusty butter knife.

Adlar threatens to make Barnabas a vampire again, then disappears. He does not tell him that he will be visited by three spirits, one representing his past, another his present, and the third the future he is risking by his present course of action, but this is in fact what happens. Barnabas goes outside, and sees a bat. It was a bat whom he first saw on this very spot who initially made him a vampire. Barnabas rushes inside, looks in the mirror, and does not see a reflection. He thinks of his mouth, and feels fangs growing there.

Next comes Megan Todd, a Leviathan cultist who with her husband Philip is fostering Michael in their home. Barnabas cannot take his eyes off Megan’s long white neck. Megan keeps telling Barnabas that he is the only one she can confide in about her concerns with the progress of the Leviathan plan; he keeps demanding ever more stridently that she leave at once. His bloodlust may explain why he doesn’t notice the continuity problem in the scene. They’ve made the point time and again that it is only while Barnabas is giving orders to her and Philip that Megan remembers that he is their leader. At other times, she thinks he is an outsider. But Megan is the only one who can tell Barnabas a story of family life in any way paralleling that which the Ghost of Christmas Present brings to Scrooge’s attention at the Cratchit house. Continuity has to go if the episode is going to fit into the form of A Christmas Carol.

Suddenly, Barnabas finds himself in an alley by the waterfront. A sign behind him says that he is next to the Greenfield Inn; we saw this sign in #439, set in the year 1796. Evidently the Greenfield Inn is a long-established, though not very reputable, place of lodging.

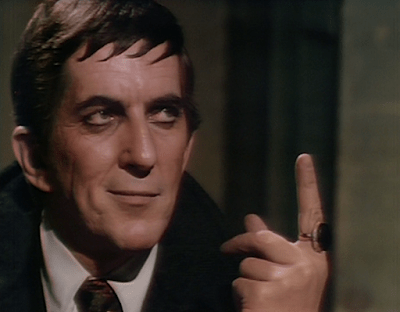

A woman approaches him. She is very aggressive about insisting he take her with him wherever he is going. He is reluctant at first, urging her to seek friends at the Blue Whale tavern, but she won’t take no for an answer. All of a sudden, he brightens and looks at her with desire. She says she is afraid of him. He asks if she wants to go, and she screws up her courage to declare that she will stay with him. He bares his fangs and attacks. The rough videotape editing adds to the violence of the scene. There is no sensuous bite, only a flash as he lunges at her and then is standing up again, protesting that he didn’t want to do it. When the camera zooms in on the bleeding marks on her neck, it is surprising to see that he didn’t rip her throat out altogether.

We cut back to Barnabas’ house. He is dozing in his chair, and the woman, displaying vampire fangs of her own, walks in through the front door. She approaches Barnabas. He awakens, and is horrified. Adlar tells Barnabas that “she is not up to your usual standards.” She’s standing right there, that’s pretty tactless. Also, she is future four-time Academy Award nominee Marsha Mason. The only other Oscar nominee Barnabas bit was Grayson Hall as Josette’s aunt, the Countess DuPrés, in #886. Hall was only nominated once, so if anything this woman is a step up for him.

Adlar makes the woman disappear, and shows Barnabas that he is not really a vampire again. With that, we see that she is a shade of a future that may come to be, not one that is already ordained. Adlar also tells Barnabas that it is not now necessary to kill Julia. But he does say that Barnabas will have to do something to ensure Julia’s silence, or else Josette will suffer. Barnabas hangs his head and says to the mirror that he has no choice to obey.